-

IPOs are hot, until they’re not. Many trade lower after going public.

-

It’s important to understand how, and if, a company can become profitable.

-

Who benefits from an IPO? In many cases, insiders and early private funders.

The last six months has seen a flurry of activity in the initial public offering (IPO) market as start-up companies seek to take advantage of a booming stock market by selling new shares to the public.

The market has recovered all of its lost ground from last October’s selloff, so companies are rushing to cash in with IPOs before the financing window closes.

Despite all the hype, there are a number of risks to purchasing an IPO.

In order to make an informed investment decision, there are several questions every investor should ask, prior to purchasing on the new offering.

Why is the company going public?

The traditional purpose for issuing new stock in the capital markets was to fund a business’s expansion or finance its operations without incurring debt.

That has changed within the last decade. Private funding has become more plentiful, many smaller, early-stage tech companies have not needed to access the capital markets to finance growth.

For the past 10 years, many start-up companies financed either by private equity or venture capital funding, were content to stay private. Publicly companies must comply with detailed reporting and disclosure requirements and have to answer to shareholders every quarter.

However, many founders and early-stage investors holding restricted stock need a way to sell their unmarketable private shares to cash out their equity stakes.

In addition, there may be employees whose compensation included significant stock options. They would be eager to tap into the proceeds that could be raised in an IPO.

The most prominent question investors should ask is, what is the primary purpose of the new offering? Will the proceeds of the IPO be used to fund expansion, or for increased operational expenses?

If it appears that the offering will primarily be a vehicle to make the founders and other insiders rich, buyer beware.

An additional risk for investors is that the founders may structure the IPO so they retain control of the corporation. Should the business falter due to their mismanagement, shareholders would have little recourse.

How will the new shares be priced?

What valuation will the underwriters assign to the company before the offering? This is perhaps one of the most crucial aspects of an IPO and presents one of the biggest risks for those looking to participate in “hot” new offerings.

The valuation will reflect the demand for the new offering as well as the company’s private valuation prior to the new offering. Lately, tech hungry investors have scooped up the shares of recent unicorns, such as Lyft and Pinterest, hoping to participate in the next potential Facebook or Google.

In terms of pricing the new issue, investors need to be mindful of separating promotional hype and Wall Street’s irrational exuberance from the company’s actual financial performance.

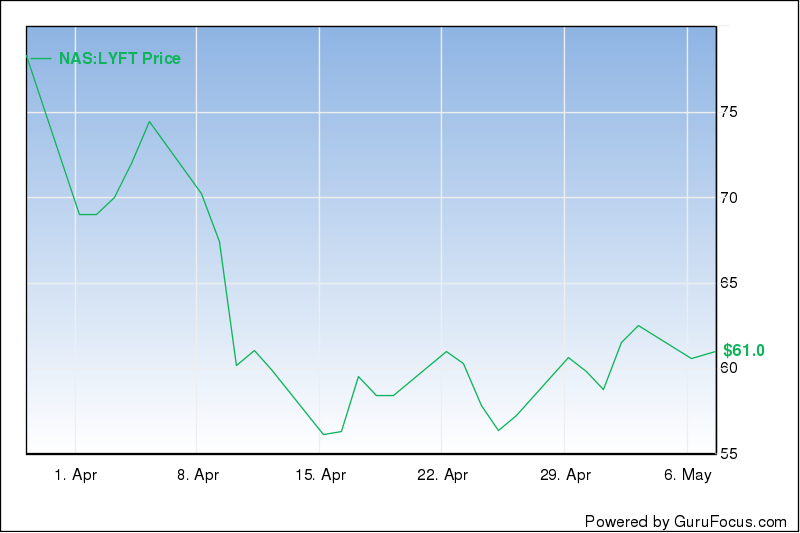

The recent disastrous IPO of ride-hailing app Lyft provides an example of how the valuation assigned by a company’s investment bankers did not comport with reality.

Lyft’s IPO debacle

Lyft had losses of $911 million the year, prior to going public. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, this represents the largest loss of any other U.S. startup in the past 12 months preceding the company’s IPO.

Although Lyft’s revenue increased dramatically to $2.2 billion in 2018 from $343 million in 2016, for the same period its losses swelled to $911 million last year from $683 million in 2016.

These numbers should have raised red flags.

Lyft’s offering price placed the company at a significant premium based on its last round of private financing. Management revised its IPO target upward in March, giving the company a valuation of more than $24 billion.

Lyft was assigned a private-market valuation of $15.1 billion last year only last year. Disillusioned Lyft IPO investors should have inquired, pre-IPO, how could that figure could have vaulted by almost 50% while the company continued to pile up losses.

Compare Lyft’s Pre-IPO history of losses with that of Pinterest, which recently went public. Pinterest had revenue of $756 million for 2018, a healthy increase from $472.9 million for the prior year. The company’s losses contracted to $63 million from $130 million in 2017.

Lyft’s IPO debuted at $72 per share, above its original contemplated range of $62 to $68 per share. After a brief flirtation in the high $80s, the stock crashed back to earth to $71. It is currently trading at $54.

A comparison of the two charts below tells a sobering tale of the two IPO’s.

The bottom line for enterprising investors?

Without any profits, it’s difficult to value the company on a rational basis. Investors should ask: Is the current valuation reasonable in light of the company’s financial performance to date?

Who makes money in an IPO?

A lot of the shares in new offerings are for those who had subscribed prior to the offering or who were among the company’s founders or initial selling shareholders.

Those who may have purchased the stock at a more favorable price are often in a better position to profit than those who buy the shares in the open market. Frequently, a new issue will pop-up in price rapidly on the first day of trading and then fall after it starts trading in the secondary market.

Data from Dealogic indicates that IPOs jumped 13.1 % on average the first day of trading but plummeted almost 14% shortly thereafter.

Given this dynamic, those who buy after the stock starts selling may risk purchasing at the high for the day, only to watch their new investment decline as quickly as it rose.

In short, early investors and founders as well as those who had subscribed to the offering and sold out were the ones who profited handsomely, not the rest of the public who bought the stock in the secondary market.

Track record of IPOs

From a long-term perspective, are IPOs a good investment? Here are some sobering statistics.

According to IPOscoop.com, of the most recent 100 IPOs in 2018, 65 declined from their initial offering price.

Those investors hungry for new deals, need to be circumspect. According to Renaissance Capital, the closing price for new shares after trading in the secondary market after the initial day’s post-IPO close dropped 16.9%.

Investors should be aware that in many cases, those who profit from new “tech” offerings are those who got in early, prior to the first day of public trading.

The example of the Lyft IPO as well as the rather dismal overall long-term return of new offerings should prompt investors to be careful about which companies are financially sound and in a position to actual grow their earnings.

This requires discipline in order to take a pass on hot issues for which many others are clamoring. Ultimately they may sink in price shortly after they start trading.