Investors with ethical concerns can now put their money where their mouth is — and still enjoy lucrative returns.

Ethical investment approaches — sometimes called socially responsible investing (SRI), environmental, social and governance (ESG) or simply sustainable investing — have seen an increase in interest from both retail and institutional investors.

The world’s largest investment manager, BlackRock, has now created several options for investors who want to avoid funding gunmakers and gun retailers in the wake of the recent U.S. school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

BlackRock also offers a range of socially responsible mutual and exchange traded funds, that have historically excluded arms manufacturers and cigarette companies, and ones which favor companies with a social bent.

Meanwhile, the number of socially responsible exchange-traded funds (ETFs) keeps on growing.

The most recent estimate puts one out of every five dollars under professional management in the United States in some variety of sustainable fund or investment practice, totaling $8.72 trillion, according to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment.

Ethical investing has long been seen as less lucrative than its less socially-minded equivalent. For instance, funds tracking only companies that sell weapons, alcohol, tobacco and gambling have long exceeded the broad market.

So-called “sin stocks” can provide a boost for equity investors. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, which managers $1 trillion in oil wealth on behalf of Norway’s citizens, found that excluding questionable stocks cost 0.1 percentage points of return per year over a decade.

It’s small difference in percentage but a huge number of dollars when you manage $1 trillion — about $4 billion in lost value.

Nevertheless, the same fund also found that excluding certain individual companies due to specific conduct problems had raised returns by 0.04 percentage points annually.

The Norwegian Finance Ministry, which broadened its ban to include big coal producers two years ago, is also questioning whether big oil companies should be excluded — a quandary for a fund that oversees wealth from oil drilling.

Price of conscience

Despite still being seen as an approach that entails sacrificing returns, ethical investment has evolved over the past few decades.

The adoption of environmental, social and governance standards by mainstream fund management has helped funds make money in a fast growing market while also making the world a better place.

Must you pay for a conscience when investing? Not necessarily.

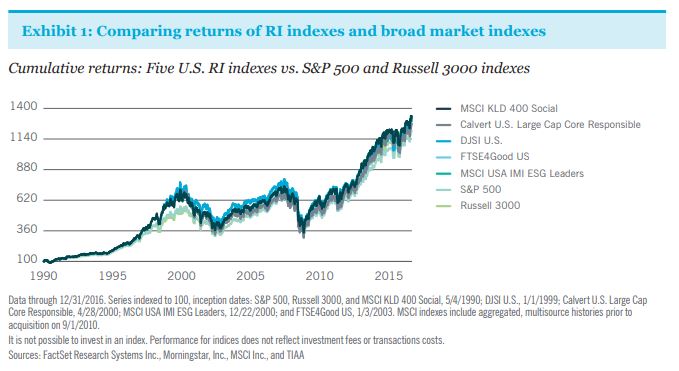

A study by TIAA, a large fund manager in the United States, found that long-term rates of return between socially responsible funds and they market indexes were comparable, with no statistical differences.

Using social criteria did not increase risk, either. However, over short-term periods there could be differences in rates of return, known as “tracking error.”

That is, a fund that attempts to match an index, such as the S&P 500, while excluding problematic stocks might not match it exactly week to week or month to month. Over time, however, the returns would similar if not the same, the study found.