I recently came across an interesting recently entitled “Old Age and the Decline in Financial Literacy.”

It was authored by a couple professors from Texas Tech and one from University of Missouri. It was published in October 2015.

Basically, the study provides empirical proof that knowledge of basic financial concepts, including investing, declines appreciably after age 60.

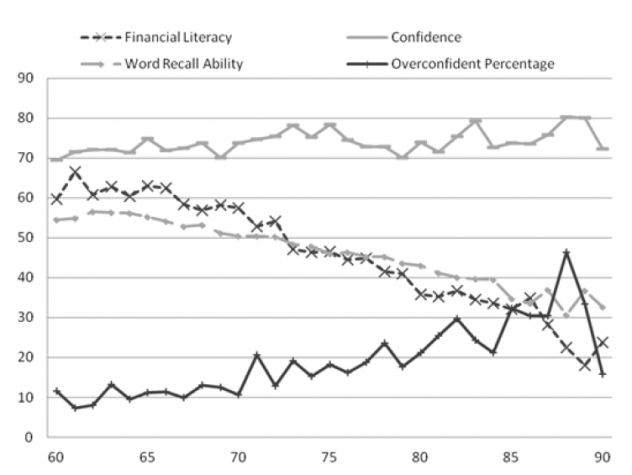

Quantitatively, it shows that financial literacy declines about 2% each year after age 60. Interestingly, it also shows that elderly people’s confidence level in their financial decision making doesn’t similarly decline with age.

See the chart below to see an overall summary of their research.

Much research has been done in this area that attempts to explain this steady decline of financial aptitude.

Gradual mild cognitive impairment, declining mathematical skills, or deteriorating spatial reasoning have all been linked to it. Regardless of the cause, the evidence is fairly strong that it does indeed occur approximately after the age of 60.

Lethal combination

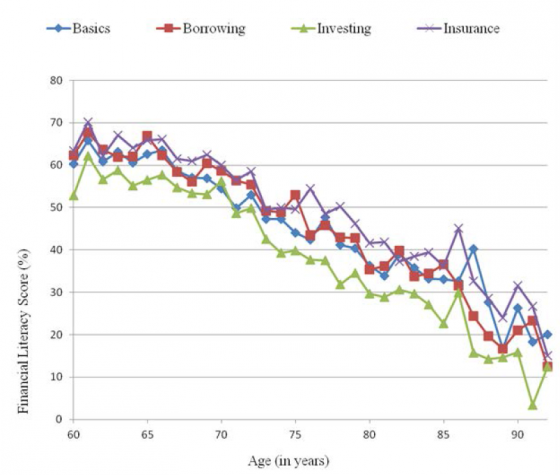

Financial literacy can be defined as the ability to understand fundamental financial concepts needed to make effective decisions.

For example, understanding the concept of a deductible in an insurance policy, or comprehending the basic characteristics of a mutual fund and how it differs from a common stock.

What is very interesting in this study, as seen in the chart above, is that overall confidence of this population set does not really decline past the age of 60, creating a potentially lethal combination of declining financial aptitude with an unchanged confidence.

They go into separating the concept of “financial literacy” into more finite categories, showing the decline in mental aptitude within each of these. (See the chart below.) It is noteworthy that financial literacy for the category of “investing” is the lowest and really declines the most as these respondents age beyond 60.

The researchers go on to stipulate that increasing confidence in conjunction with reduced cognitive abilities can, in large part, explain the poor overall investment decisions people often make in their later years.

Given that financial advisors are probably in discussions with people either within this age range or rapidly approaching it, the empirical work presented here is indeed something to keep in mind.

It points to the argument that many people in their elder years or entering their elder years may need the professional services of a financial advisor or a registered investment advisor as stewards of their capital for the remainder of their lives.