Most of us currently working understand that in order to have a sufficient income for retirement you need to be diligent about making annual contributions to your retirement accounts.

These same people however, may balk when you tell them that receiving regular raises — actually earning more money — can instead lead to less money in retirement. Yet a recent retirement investment industry study found that individuals who receive regular raises do actually have less money to live on once they retire.

The idea of actually have less retirement savings from cumulative income raises is counterintuitive. The main reason that increasing income leads to less later on is psychological, not financial.

According to Morningstar, the phenomenon of “lifestyle creep” leads to an expectation of a more enhanced style of living, which then leads inexorably to higher living expenses. Those added costs go unnoticed by most people throughout their working years.

The study also found that the desire to match increasing income from raises with a better lifestyle, that is, with more consumption, is common among those saving for retirement.

“The income rise quickly becomes part of your expenses, and you’re back to living, for many people, paycheck to paycheck,” says Steve Wendel, co-author of the report. “While the expenses leave a lasting trail, the happiness from those changes in your lifestyle often don’t. They become part of the furniture of your life, and you just don’t notice them after a while anymore.”

The report, “More Money, More Problems: How to Keep a Bigger Paycheck From Spoiling Retirement,” urges workers to get in the habit of saving a larger portion of their additional income from raises to help mitigate the negative impact of “lifestyle creep” on retirement.

This is easier said than done. Most workers over time accept additional expenses from their elevated lifestyle and maintain the same percentage rate of savings prior to the raise.

The difficulty presented by lifestyle creep is that individuals may maintain a constant savings rate, prior to and after the raise, but that still will be insufficient to fund for their elevated lifestyle in retirement.

The report notes: “Savings rates … generally need to increase in both relative and absolute terms to account for new retirement needs once a person’s lifestyle adjusts to the additional income, but many people don’t do that.”

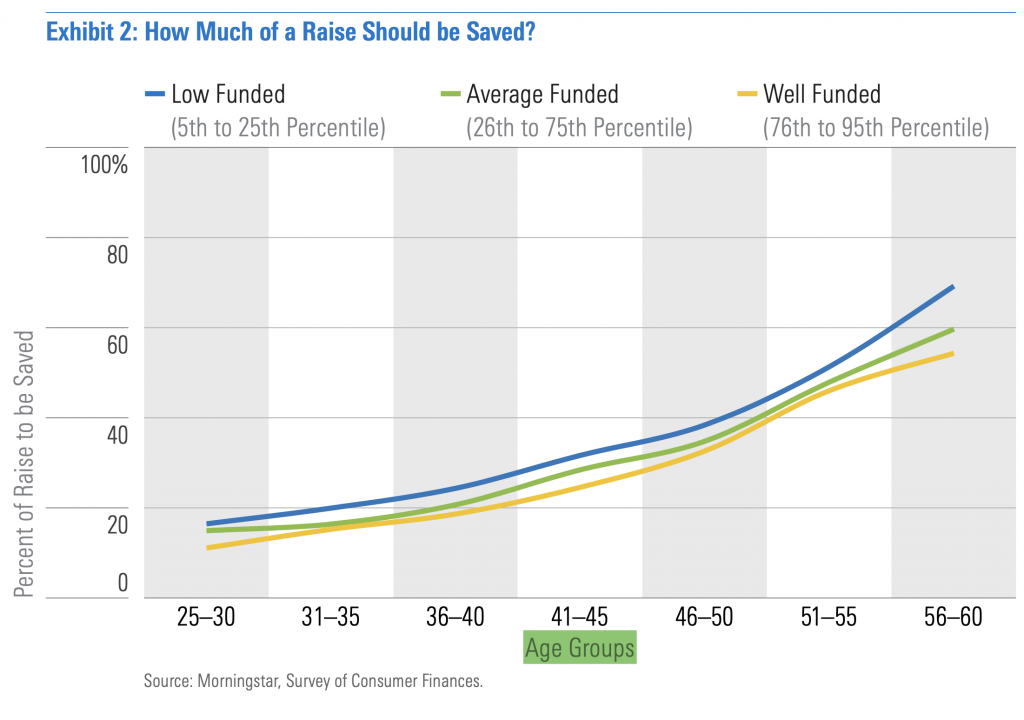

The study used data from the Survey of Consumer Finance to determine how much of a 5% raise would need to be saved to match pre- and post-raise retirement standards. The purpose of the model was to determine the additional cumulative amount that needed to be saved to fund the new, more expensive, retirement lifestyles.

The findings suggest that older workers should save more to keep up with their escalating standards of living, regardless of how much they have saved already. One aspect of this analysis is self-evident, as it is a question of simple arithmetic.

The older an individual is the less time he has to play catch up in terms of achieving the necessary rate of savings required to fund an enhanced retirement lifestyle. Additionally, the shorter years to retirement diminishes the compounding period, or number of years to post annual returns or growth in an individual’s investment portfolio

The graph below illustrates the results of the study between three test groups: those who are well funded, average funded and well-funded. The graph shows the percentage of an individual’s raise that needs to be saved to match the heightened standard of living the raise brings, with the expected standard of living in retirement.

Achieving your savings goals

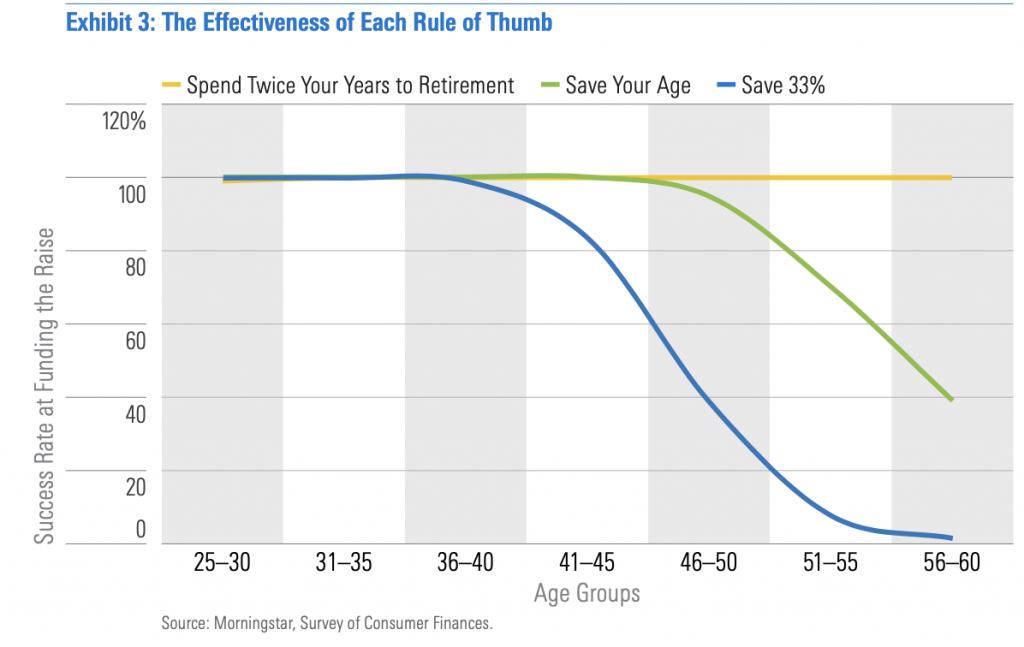

The study presents three guidelines to help savers determine how much of a raise should be saved to insure they secure their goal of maintaining in retirement the standard of living to which they have been accustomed.

- Spend twice the number of years to retirement. If you are going to retire in 10 years, you should spend 20% of your raise and save the remaining 80% for retirement.

- Save your current age, as a percent of the raise received: If you’re 50, you should save 50% of the raise.

- Save at a minimum, 33% of your raise: If your take-home pay increased by $1,000, you should save $333 of that new income for retirement.

The effectiveness of each of the three rules is depicted in the graph below.

As the chart shows, rule number one “spend twice your years to retirement” had the highest success rate across all age groups. The “save your current age rule” is effective until age 45, then it drops significantly thereafter.

Rule three, “save 33% of your raise” begins to decline in effectiveness at approximately age 35.